It’s a Sunday in 1971, and a shy 11-year-old kid is wandering around Hackney with his camera, looking for something to photograph. Spotting a Palestinian Liberation Organisation rally, he stops to take pictures and promptly takes his prints to a photo agency on Fleet Street. Incredibly, one of them ends up on the front cover of the Daily Mirror, pocketing the child snapper the princely sum of £16.

There are many remarkable stories like this surrounding Dennis Morris and his photographs at his three-floor exhibition Music + Life. Born in Jamaica, Morris moved to London before encountering photography through a camera club at his local church, St Mark’s in Dalston. There was, perhaps as a consequence, a religiosity about the way Morris devoted himself to the medium (he was dubbed “Mad Dennis” for preferring photography over football). Around the same time as he shot the PLO protest, Morris had also set up a humble commercial photo studio in the bedsit he shared with his mum – he pinned up a white sheet and borrowed a tungsten spotlight from St Mark’s. A few of these pictures from the early 1970s feature in the show, striking in their maturity and command of the camera. He understood how to make his subjects look and feel good.

The show highlights not only Morris’s instinct for a decent picture but his enterprise from such a young age, and his knack for being in the right place at the right time – the secret ingredient of any master documentary photographer. That spirit of determination and robust sense of self-belief seems to guide Morris in his photographs, to look where no one else is looking. A feeling of self-worth was what attracted him to photographing, and his subjects – whether impoverished residents of 1970s Hackney or globally revered musicians – have it in spades.

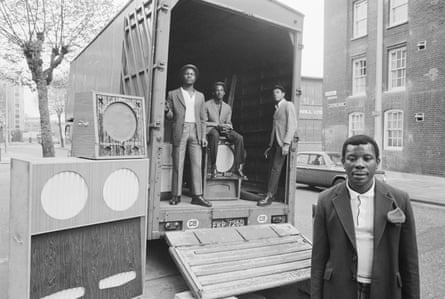

There are the sharply-dressed “box men”, transporting sound systems across town, and couples at blues dances, where whisky shots and plates of curried goat cost £1. Even when the walls are peeling and decrepit, “dignity and pride” is in abundance, as the title of one portrait of an elegant male figure in Hackney declares.

By the age of 14, another cleverly choreographed encounter led Morris to make the body of work that has eclipsed everything else he’s done – his portraits of Bob Marley. Morris went to the Speak Easy Club on Margaret Street one day in May 1973 and hung around waiting for Marley to show up for soundcheck. It coincided with a monumental moment for the reggae star, who was in town with the Wailers to play their first London gigs as part of the Catch a Fire tour. The four-day run at the club was sold out. Morris of course managed to meet Marley – and from that exchange, Marley invited Morris to join the group for the rest of the tour.

Music + Life includes Morris’s iconic 1973 triptych portrait of Marley smoking (among the many things Marley taught Morris, the photographer has said, was how to smoke a joint). Other strikingly intimate images by the teenager that make you think that Marley, in his Adidas SL72 trainers, was an avuncular figure for this kid suddenly propelled out of Hackney and into the world.

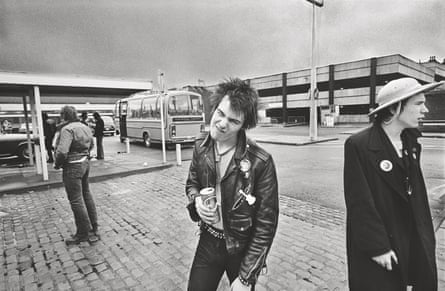

Marley opened up a world to Morris, who went on to photograph every major reggae star of the era, then later the punk scene too. These photographs, including brilliant ones of the Sex Pistols, take up a whole floor of Music + Life. They are the work Morris is best known for, published as magazine and album covers, merchandise and posters, taken in Kingston and London.

His portraits draw out the personas of reggae’s bigshots. There’s a controversial publicity photo of Steel Pulse, who are dressed as Ku Klux Klan members for the sleeve of their 1978 single of the same name. There’s the flash lighting up Big Youth’s dreadlocks, the lens pushed close to his face, and a shot of a majestic Dennis Brown toking. The photographs crackle with the heat of dancing, the fever of nights at recording studios. You can almost smell the marijuana.

The familiarity of these iconic images is part of the appeal of seeing them now in the gallery. But it’s those early photographs that serve as a reminder of the harder realities of his roots. Many of these works were published in Morris’s 2012 monograph Growing Up Black but are less widely known and appreciated. They show how his resourcefulness and inventiveness developed from a lack of opportunity and a need to survive.

A boy begging on Dalston’s smoky, broken and desolate Sandringham Road in 1976, which is barely recognisable today, possibly presents a stirring moment of identification. The boy is not much younger than Morris when he took the picture. The same feeling emanates from a portrait of a young Sikh girl carefully holding a newborn baby relative in a shop in Southall in 1974 – one of Morris’s rare documents of the area’s Sikh community. It’s there in the choirboys, youths at demonstrations, squatter kids or those residing at Black House on Holloway Road.

These images say an awful lot, helping us understand how the capital has changed in a generation. This is Morris the entrepreneurial young spirit, away from the stardom and success. And for all the visible hardship and trenchant tension in these images, it’s clear Morris loved being in these places with these people, and they loved him back.

5 hours ago

2

5 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)