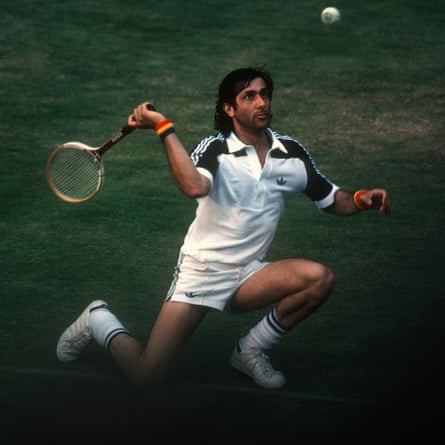

There was never a dull moment with Ilie Nastase. Walking across Centre Court before his first-round match at Wimbledon in 1980, the Romanian had his eyes firmly set on a box at the side of the court. He bent down to look at the device, the crowd tittering as he examined it. This was no ordinary box. It was a £2,000 machine installed to improve officiating and eliminate controversial decisions. But, just like the move away from line judges this year, not everyone was impressed.

Now for the science bit. Invented by Bill Carlton and Margaret Parnis in the late 1970s, the machines – for ever known as Cyclops – were only used on service line calls. Two boxes were set up either side of the service box backline on both sides of the net, one sending infrared lines across to the other. If any beams on the “out” side of the line were broken, a red light would show and a bleep would sound to the line judge, who sat beside the box wearing headphones. The official would shout “fault” as usual and everyone would happily accept the decision and move on. Well, that was the plan.

There was curiosity and suspicion when the devices made their debut at a grand slam during Wimbledon in 1980. “Science received a frosty welcome at Wimbledon,” wrote David Irvine in the Guardian as the rain-hit tournament started. Nastase was one of the doubters. During his straight-sets win over British player John Feaver, the two-time major winner questioned the accuracy of the “magic eye” or “spy eye” as the press dubbed it.

“Two calls were definitely wrong,” said Nastase, who had bounced balls on the box and threatened to hit it with his racket. “John Feaver told me about another. The machine must have been made in Russia. I don’t think it will end disputes about line calls. I will wait and see.”

Butch Walts was even more scathing after his straight-sets defeat by No 2 seed John McEnroe. Known for his big serves of 120mph, the American raised concerns with tournament referee Fred Hoyles, asking him to turn off the new devices. “It is supposed to be foolproof and it is not,” said Walts. “You can have a linesman removed for not doing his job properly, so why shouldn’t the magic eye be turned off? It may be alright in concept but it’s useless in practice. The bleep occurs if the ball lands up to six inches over the line but on yesterday’s evidence there are grave doubts about its suitability.”

As the sceptics mounted, Carlton was forced to defend his new invention. “Some players will argue with anything,” he said. “I don’t think my machine makes mistakes within a tolerable limit. It is accurate to an eighth of an inch.” Sometimes the mistakes were avoidable. In one particularly embarrassing moment, a line judge forgot to turn on the magic eye during Björn Borg’s match against Ismail El Shafei – the exact same issue that would affect the match between Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova and Sonay Kartal 45 years later.

As the years progressed, the devices remained controversial. “The electronic eye is not perfect,” wrote Malcolm McIntosh in the Observer before Wimbledon in 1987. “Last year spectators were treated to a bird landing on court and receiving a line call. The equipment is so sensitive that even a strong wind can set it off. The light beam passes just two centimetres above the grass and on occasion the wind has blown blades of grass up to trigger the bleeper.”

Despite arguments over the introduction of Cyclops, many pondered whether technology could be developed further to help with all line calls in tennis. McIntosh urged caution. “Before it can be installed on all white lines the equipment must be able to distinguish between a ball, a foot, a racket and a bird.”

The discussions were not just limited to tennis. With the growth of American Football in the UK during the mid-80s, television viewers were introduced to the concept of a Replay Official to adjudicate on decisions taken on the field. When Football League referee officer John Goggins was asked about football adopting the same approach in September 1986, his reaction was telling. “God forbid. We would take away the human element of a game designed for human beings with human emotions,” he answered emphatically.

Rugby union referee David Bevan agreed:: “It is moving towards the days when you won’t have referees, you’ll have computers doing it.” Rugby league referees assessor Joe Manley feared video decisions creeping into the sport, as it had started to in Australia. Other areas of technology in sport were also under consideration. Test and County Cricket Board chair Raman Subba Row suggested umpires wearing small watches with video screens to potentially help them with run outs.

The mind boggles at what the doubters in the mid-1980s would make of technology in sport in the modern era. Yet, despite the furore, Cyclops was here to stay, with the US Open soon following suit and using the machines. Eventually Hawk-Eye arrived in the 21st century, leading to the retirement of Cyclops – at the 2006 US Open, and Wimbledon and Australian Open a year later – as technology moved on.

Carlton knew where his invention was leading. “The time will come when it will be the final decider of what is in and what is out,” he said in 1980. Cyclops never quite reached that stage but it started a process that has led us to where we are today: AI taking the place of human line judges … and players doubting the accuracy of the technology. Maybe the past isn’t such a foreign country after all.

This article is by Steven Pye for That 1980s Sports Blog

6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)