Petra Costa was rewatching footage of what has become a historic speech made in 2021 by Jair Bolsonaro, the then Brazilian president, when suddenly she noticed something that went largely unnoticed at the time. Addressing thousands of supporters in São Paulo, the far-right leader lashed out at a supreme court justice, and said he would only leave the presidency “in prison or dead”. This statement is now cited as evidence against Bolsonaro, who is currently on trial, accused of attempting a coup to overturn his 2022 election defeat to current president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Bolsonaro denies these allegations.

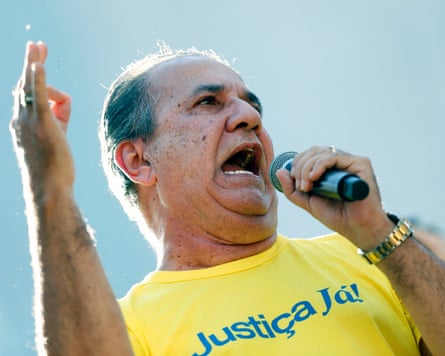

But what caught Costa’s eye in the footage was Bolsonaro’s gaze. As he shouted into the microphone, the paratrooper-turned-populist repeatedly looked – seemingly seeking validation – at one particular man in his entourage: the televangelist Silas Malafaia. In response, the evangelical leader appeared to be lip-syncing along to the president’s every word. “I watched the scene many times,” says film-maker Costa, “and the only conclusion I can draw is that Malafaia wrote Bolsonaro’s speech. If not, how could he have known every word?”

This footage provides a compelling moment in the 41-year-old’s new documentary, Apocalypse in the Tropics. Oscar-nominated for The Edge of Democracy, her previous film about Brazil’s descent into populism, Costa this time explores the growing influence of evangelical leaders in the country’s political process. “This film is about Brazil,” she says, “but the story is part of a global phenomenon of religious motivations undermining democracies. We’ve seen the rise of religious fundamentalism joined by a nationalist, conservative and extremist agenda all over the world – from the US to Russia.”

In many ways, the new film is a continuation of the critically acclaimed previous documentary, which charted the unravelling of the democratic fabric of Latin America’s largest country with rare, behind-the-scenes access to key moments in recent politics, including the rise to power of backbench congressman Bolsonaro.

Now, through the lens of what she describes as the growing influence of Christian religious fundamentalism, Costa updates that story, covering events such as the January 2023 riot in which Bolsonaro supporters ransacked the presidential palace, Congress and the supreme court. As investigations by the federal police and the public prosecutor’s office later concluded, the uprising was allegedly the climax of a coup attempt that began while Bolsonaro was still in power.

A central figure in Apocalypse in the Tropics is 66-year-old Malafaia, one of Brazil’s most prominent preachers, with whom Costa and her team, which includes producer Alessandra Orofino, conducted about a dozen interviews. Although Bolsonaro had contact with many other Christian leaders during his four-year term, the film-maker believes none wielded as much influence over the president as Malafaia. In 2022, the evangelist even joined the Brazilian president’s delegation to London for Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral. “Next to him,” she says, “Bolsonaro almost seems diminished – like a child in front of a master.”

In September 2018, just two days after being elected, Bolsonaro took to the stage at Malafaia’s church, greeted by chants of “Myth! Myth!”, as he is known, from the hundreds of worshippers present. Before handing the microphone to him, Malafaia paraphrased a passage from Corinthians, saying: “God chose the foolish things to shame the wise … God chose the lowly things, those of little value, the despised, the discarded, those that are nothing … to shame the things that are – so that no flesh may boast before Him. That’s why God chose you!” He then pointed to Bolsonaro, who listened with a furrowed brow.

Apocalypse in the Tropics also captures a private meeting between the two, inside the presidential office, in which the preacher recalls officiating at Bolsonaro’s wedding. The far-right leader identifies as Catholic but his wife, Michelle, is a Baptist. Malafaia says: “We were waiting for the bride … and this guy came up to me. I say ‘this guy’ because we’re friends … and said, ‘Malafaia, I’m going to run for president.’ And I said, ‘Are you out of your mind?’ … I left thinking, ‘This guy is crazy.’”

Shortly after, Costa asks the president if he will follow through on his promise to nominate someone “terribly evangelical” to a vacant supreme court seat. “Yes,” he replies. “Many people come to us with fantastic CVs, but the first requirement is to be evangelical. And, of course, after that, also having legal knowledge.” Bolsonaro kept his promise, appointing another preacher to the court. In fact, such was the religious influence over Bolsonaro’s administration that Costa found herself wondering if Brazil was turning into a theocracy – a process she believes was halted by Lula’s election, although the risk, with new elections coming next year, “remains very much alive”.

Although the former president is barred from running until 2030 by an electoral court ruling, polls suggest that any candidates backed by him – including his wife or one of his sons – could pose a serious challenge to Lula, who has already confirmed he will seek re-election.

We approached Bolsonaro about all the claims in this article but his team did not respond.

The film weaves together interviews, archive footage and Costa’s narration, accompanied by closeups of apocalyptic paintings such as the depictions of the Last Judgment by Fra Angelico and Hans Memling. The rise of evangelicals in Brazil is described as “one of the fastest religious shifts in human history”. In recent years, alongside a congress that grows more conservative with each election, gospel singers and religious influencers have become superstars, while Brazil’s still immensely popular telenovelas, or soaps, have increasingly incorporated evangelical characters and storylines into their plots.

Some experts even predict that Protestants, Baptists, Pentecostals and neo-Pentecostals will at some point become the majority in Brazil – the country with the largest Catholic population in the world. The documentary says they are now “over 30%” of the population, although new census data released last month – after the film had been finalised – showed they make up only 27%, which nonetheless marks a significant increase since 1970, when they were 5.2%. Catholics declined from 91% to 57% over the same period. As they make up more than a quarter of the population, evangelicals represent a major challenge for any non-conservative candidate, such as President Lula, who faces deep resistance from them.

Apocalypse in the Tropics depicts an exchange between a mother and her teenage daughter inside their home, during Brazil’s 2018 presidential campaign. The mother says she plans to vote for Bolsonaro “because he’s a man of God”. She adds that Lula, although “also a man of God”, is “from Candomblé” – an Afro-Brazilian religion that faces persecution from some Christian groups. In reality, Lula is Catholic, but he has expressed support for Afro-Brazilian faiths.

The mother then asks her daughter to look up a photo of Lula “receiving the sword of Xangô”. In fact, it was an axe – a symbol of the orixá, a divine spirit associated with justice. It was a gift to Lula from a university rector in 2017. As the girl begins typing “Lula” on her phone, the autocomplete turns up phrases such as “being consecrated to the devil” and “supports unisex bathrooms”.

The film is not, however, intended as a critique of any specific religion, says Costa, but rather of the “political manipulation of faith, which poses one of the greatest threats to democracies around the world”. She recalls witnessing firsthand how the church can positively influence people’s lives, citing preachers who provided “physical, emotional and spiritual care” in favelas during the pandemic, offering food, jobs and even paying for ambulances.

“What we need is a more nuanced perspective,” Costa concludes. “There won’t be a war in which good defeats evil, not from the right, nor from the left. There must be dialogue – and that’s complex and difficult.”

4 hours ago

2

4 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)