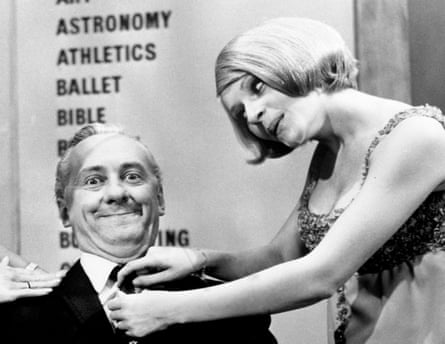

One of the biggest TV hits of the 1960s was Double Your Money, a kind of low-fi precursor to Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?. Its presenter, Hughie Green, was a titan of family entertainment who drew audiences of more than 8 million to the ITV gameshow, in which contestants chose whether to double their prize pot between questions.

It was, of course, all about the cash, even if TV-rich in those days involved maximum winnings of £1,000 (about £18,000 in today’s money). The show’s baked-in avarice made the entry in the TV Times for 7pm on 8 November 1966 surprising: “Double Your Money visits Moscow with People to People … the first ever western quiz game in the Soviet Union.”

For two consecutive Tuesdays, millions of Britons watched Green and his sidekick Monica Rose present a heavily adapted version of the show from a rudimentary studio in the House of Friendship, a mock-Moorish castle near the Kremlin that served as a theatre for communist propaganda.

Subtitled “People to People” in the listings, the show was renamed “Do You Want to Go On?” in Moscow. Money did not feature. Instead contestants competed for points, which could be exchanged for state-made goodies such as toasters and televisions.

The recordings were beset with technical difficulties. Lights went out, speakers failed. “But what impressed me most was the excitement and enthusiasm of the audience,” recalled show producer Bill Costello in 2018. “To them the show was unusual, different and original and they really got carried away by the competitive spirit.”

Viewed from today, the export of a British cash-prize gameshow to Moscow seems fanciful, not least given the current state of relations between Russia and the west. Yet they were in keeping with a wider tradition of cold war cultural exchanges from 1955 until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. This soft-power tit-for-tat involved the shipping of entire ballet, opera and theatre companies as respective governments, and a string of impresarios, swept back the iron curtain to reveal the best each side had to offer.

The cultural contest was instigated in Moscow after the death of Stalin in 1953. His successors quickly set about softening relations with the west. “They needed to open up, but they wanted to open up in a kind of controlled way,” says Sarah Davies, a history professor at Durham University, who is working on a book about these exchanges.

Within weeks of Stalin’s fatal stroke, Lilian Hochhauser, a London impresario with Russian heritage, began to shuttle top dancers and musicians between the countries, including Mstislav Rostropovich, Dmitri Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten. Hochauser, who is now 98, said in 2019 that a mutual cultural appetite that had flourished during the Anglo-Soviet allyship in the second world war had only grown under Stalin. “Everybody wanted to see the folk-dance companies from the Ukraine, the Moiseyev Dance Company,” she told the Times. “Everything was exotic. Because it had been such a closed book for so long.”

London initially feared the propaganda potential in such swaps and used the British Council to exert its own control. The first sanctioned visit arranged under its auspices came in 1955 when the 30-year-old director Peter Brook took Hamlet to Moscow, with Paul Scofield in the leading role. It was doubly symbolic; Stalin had hated Hamlet. “It had almost been taboo,” Davies says of the play.

The Soviet regime also sought legitimacy in the patronage of such heavyweights as Scofield, Britten and even Hughie Green. Stars would be given tours of key Soviet sites, captured by news crews whose films could be narrated as each side saw fit. “How do they live, these mysterious human beings, once our wartime allies but always an unknown quantity to us,” a narrator says in clipped English over a 1965 Pathé news film of Olivier touring Moscow, where the National Theatre was staging Othello a year after the Bolshoi had visited London.

By then, the risks of these exchanges had become dramatically apparent, with the defection of Rudolf Nureyev during a Kirov Ballet tour of Europe. Before that, in 1958, MI5 were caught on the hop when Michael Redgrave secretly met his old Cambridge friend and notorious double agent Guy Burgess during another tour of Hamlet in Moscow. In an intercepted letter to his mother, Burgess said the men had enjoyed “fine gossips” and that Redgrave had been “much better than Paul Scofield” as Hamlet. But such high-profile brushes with scandal failed to close the curtain on the project, which had been formalised in 1959 with the Anglo-Soviet Cultural Agreement between the British Council and its Soviet counterpart.

It wasn’t all Shakespeare and ballet. Some cultural exchanges continued to take place outside the official agreement. The British Council had no role in the Double Your Money episodes, which were hosted by Moscow Television during a relative thaw, before the Red Army crushed the 1968 Prague Spring, an attempt by Czechoslovakia to loosen Moscow’s grip. This perhaps partly explains the knockabout tone of the TV Times coverage of the enterprise. “Caviar for breakfast? Well, why not? At 7s 6d for a large dollop, it’s a fabulous buy,” wrote Dave Lanning, a columnist and ITV darts commentator, who joined Green for a tour of Moscow.

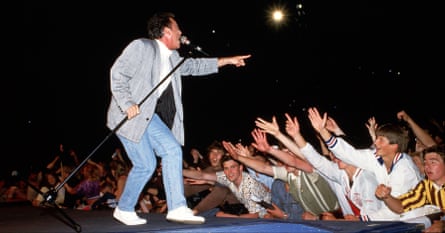

In 1976, Cliff Richard became the first major western pop musician to visit Moscow. He later recalled being given an ornate tea urn in exchange for a pair of his blue jeans. To the delight of fans who had devoured bootlegged records by the Beatles et al, more big names followed in the 1980s, particularly during glasnost, Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempts to open up. Elton John made the trip. Billy Joel crowd surfed in Leningrad while draped in the American and Russian flags.

after newsletter promotion

Some culture was considered beyond the pale for longer, most notably modern art. “Because Soviet art was generally socialist-realist, they found western abstract art a bit of a challenge,” Davies says. But, by 1988, James Birch, a provocative 32-year-old London art curator, spied an opportunity. He had befriended Sergei Klokov, an enterprising KGB agent, and conspired with him to put on a Francis Bacon exhibition in Moscow. Birch says the artist, whom he had known since childhood, was buzzing. “He even went out and bought himself a Walkman and learned Russian on cassette,” he says. In the end, the notoriously capricious Bacon decided not to go, but 400,000 Russians filed through the city’s Central House of Artists to see his work.

Birch and Klokov teamed up again in April 1990, in the dying days of the USSR, to take Gilbert & George to Moscow. The exhibition was another hit, and open to interpretation. While looking at Coming (1983), in which the artists look up at a sky filled with flying underpants, a Russian man told Birch he thought it represented the west invading Russia, with the pants symbolising war planes or parachutes.

Whether these exchanges played any significant role in hastening the demise of the Soviet Union remains a matter of debate. Davies says cultural figures who appeared through the iron curtain sometimes overestimated their influence. “It was part of this whole triumphalist narrative that the west undermined the Soviet system because we presented this better, brighter alternative, but I think a lot of scholars challenge that,” she says.

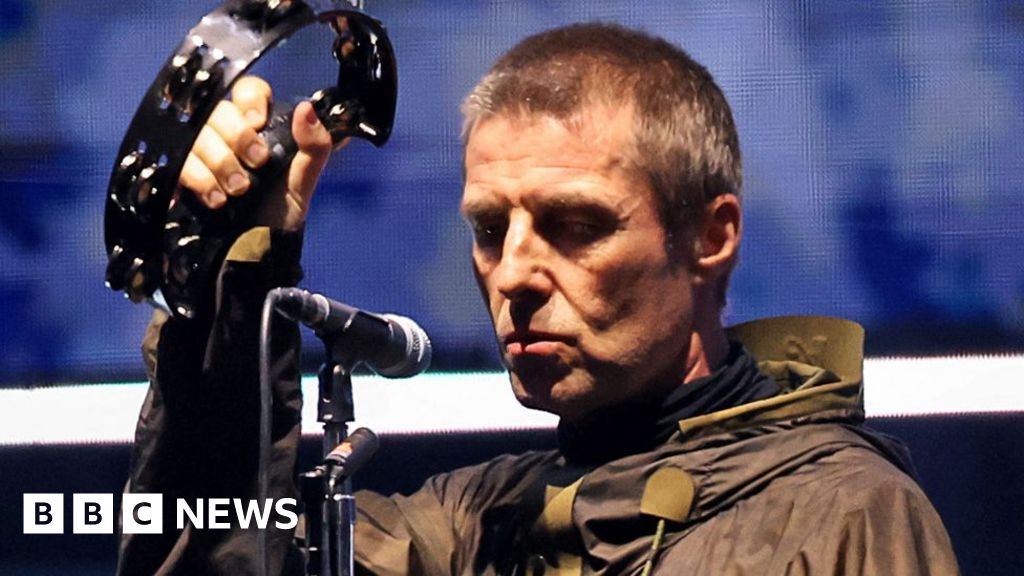

The tradition of cultural exchanges endured after the cold war, and visits continued to serve the Kremlin as an opportunity to sell its legitimacy on an international stage. In 2003, Paul McCartney performed Beatles hits in a landmark Red Square concert. Vladimir Putin, three years into his presidency, was enthusiastic. Over tea, he told McCartney the Beatles’ music had been “like a gulp of freedom … an open window to the world”. When Putin arrived halfway through the gig, McCartney played Back in the USSR, his 1968 parody of western patriotism.

Two decades later, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has plunged cultural relations into a new ice age. “It reminds me of the Stalin years, when there was no contact at all,” Davies says. But she has noticed a slight softening. In September, the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko is due to perform at the Royal Opera House in London, three years after New York’s Metropolitan Opera dropped her for refusing to denounce Putin, whom she had supported (she later criticised his invasion and sued the Met).

In the meantime, the battle for ideas is playing out on new stages. Godfrey Cromwell, a hereditary peer and the director of The British East-West Centre, formerly the The Great Britain-USSR Association, says the use of social media as a propaganda tool has become more important than physical exchanges. Such accounts, he says, “can deliver focused messages to far larger audiences at far less cost”.

Regardless of their diplomatic potential, cultural exchanges have always opened windows to the people behind the regimes. As Bill Costello put it, decades after Double Your Money’s unlikely jolly in Moscow: “It was an incredible experience and a very human one – because underneath all the language problems and differences in culture it certainly proved to me that people are the same the world over.”

5 hours ago

2

5 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)